Pine Creek and Anna Mae trails are closed due to high creek levels, as well as under the natural bridge.

Science

In many of Arizona’s wild places, the powerful forces of nature are displayed so prominently that even the untrained eye can see the evidence. Believed to be the world’s largest natural travertine bridge, Tonto Natural Bridge is one of those dazzling displays.

The Geologic Formation of Tonto Natural Bridge

The land was molded by multiple cycles of lava flows after volcanic eruptions, sculpted by the force of erosion, compressed under seawater, and eventually cracked open after its basalt cap was shifted by faults. If you traveled back millions of years in time, you would see chaotic periods and dramatic changes in the landscape.

Today in Arizona, much of that geologic chaos has subsided, leaving us to marvel at the glorious wonder it left behind. The bridge stands 183 feet high over a 400-foot long tunnel that measures 150 feet at its widest point.

Visit Tonto Natural Bridge State Park and you’ll be surrounded by peaceful scenes: the musical waterful that drips gracefully over maidenhair ferns, fish that lazily swim in the pools of Pine Creek, the stillness that settles in the cool shadow of the bottom of the bridge, and lush vegetation that grips to the sides of the craggy canyon.

Even in this serene setting, keep your eyes peeled for some distinct geological features that tell the story of how this dramatic landscape was developed.

Five Stages of Formation

To understand the complex natural process that sculpted the bridge we see today, explore the five distinct stages of its formation, from the earliest emergence of rock layers to the erosion of a travertine dam. Each stage has played a crucial role in shaping the geological marvel that we witness today.

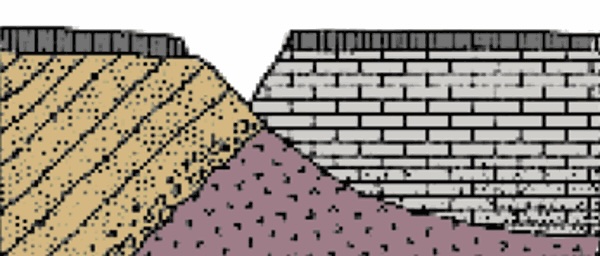

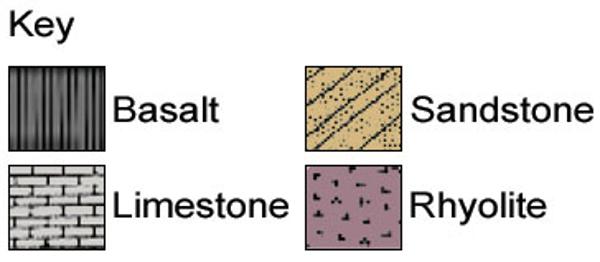

Stage 1: This west side of Pine Creek was formed by a flow of lava in the form of rhyolite, a red, coarse-grained volcanic rock. The older rock then eroded, leaving the purple quartz sandstone. The rock layers were compact under pressure and gradually became solid rock, then they tilted and faulted—when rock layers break rather than fold, and eventually eroded.

Stage 2: This area was covered by seawater, leaving sediment of sand and mud composed of lime deposits.

Stage 3: Following the erosion of the sedimentary layers, volcanic eruptions covered the rock layers with lava, forming a basalt cap.

Stage 4: Over the years, by the natural process of erosion, the basalt cap broke down and was shifted by faults, creating the narrow Pine Creek Canyon.

Stage 5: Geologists estimate that over 5,000 years ago, precipitation began seeping underground through fractures and weak points in the rock, resulting in limestone aquifers. Springs emerged as a result of aquifers carrying the dissolved limestone and depositing calcium carbonate to form a travertine dam. Water eroded through the travertine and ultimately formed Tonto Natural Bridge.

Travertine: Rocks From the Water

When you visit the natural bridge, look up and observe how the light tan-colored rock almost seems to spill and drip down its walls. This rock is called travertine, and it’s a finely crystalline form of dissolved limestone. Travertine is formed by the deposition of calcium carbonate in fresh water. It is a chemical sedimentary rock derived from the evaporation of spring water rich in calcium carbonate.

As water tumbles over rocks and rain percolates through the ground, the naturally slightly acid water dissolves out calcium carbonate from the underlying limestones. This solution eventually gathers in the aquifer that supplies the area’s springs. As the spring water emerges and comes in contact with the air, carbon dioxide is released, not unlike opening a soda pop bottle. What goes into solution can precipitate out, and calcite is forced out of solution when the water evaporates forming travertine. Calcite is a mineral having the formula CaCO3, calcium carbonate.

Travertine, a form of calcite, is mostly white when freshly deposited but turns gray upon weathering. It can also be colored red, brown, or yellow by impurities such as iron compounds. A mixture of calcium carbonate and plant life can also form travertine.

Many hot springs and geysers deposit travertines. The same process forming travertine stalactites and stalagmites can be found in abundance in caves such as Kartchner Caverns State Park in southern Arizona.

Geology and YOU!

When you visit the bridge, put on your science cap and make observations on the geology you can see all around you!

On the observation deck, pause to look at the top of the bridge as the water trickles down from the overhead spring. Notice the changes in the travertine ceiling and walls of the bridge all the way down to the bed of Pine Creek rushing below. Walk through the bridge and observe where the light-colored travertine meets the deep red rhyolite. Keep your eyes peeled for imprints of leaves and enveloped rocks in the travertine.

While exploring under the bridge, step carefully! This rock has been polished by flowing water from the natural springs in this area for thousands of years and is very slippery.

Is your imagination captured by the incredible geologic history evidenced at Tonto Natural Bridge State Park? We hope so! During your visit, you can learn even more by chatting with our park rangers and volunteers.

To enrich your experience, consider bringing a camera and notebook to document your observations, a magnifying glass to take a closer look at the information that every stone has within it. Additionally, you can purchase a geology pocket guide or more in-depth geology book from the park's gift store.

Ecology Overview

Tonto Natural Bridge State Park is located in central Arizona near Payson. It is believed to be the largest natural travertine bridge in the world. The bridge stands 183 feet high over a 400-foot long tunnel that measures 150 feet at its widest point. There are three hiking trails, a picnic area, and a group use area.

The vegetation in the park is dominated by oak (Quercus arizonica, Q. gambelii, Q. turbinella, Q. undulata, Q. chrysolepis, and Q. emoryi). Other trees and shrubs include Cottonwood (Populous fremontii), Arizona sycamore (Plantanus wrightii), Juniper (Juniperus deppeana and J. osteosperma), pinyon (Pinus edulis), alder (Alnus oblongifolia), hackberry (Celtis reticulata), silktassel (Garrya wrightii and G. flavecens), and sumac (Rhus trilobata and R. ovata). Prickly pear (Opuntia macrorhiza), century plant (Agave parryi), and beargrass (Nolina microcarpa) are also found in the park.

Tonto Natural Bridge State Park provides habitat for animals, insects, and birds both small and large. There are five kinds of bat (Myotis velifer, M. californicus, M. lucifugus, M. yumanensis, and Euperma maculatum) living in the park. Other mammals include bobcat (Felix rufus), cottontail (Sylvilagus sp.), black bear (Ursus americanus), coyote (Canis latrans), gray fox (Urocyon cinereoargenteus), elk (Cervus elephus), javelina (Tayassu Tajacu) and mountain lion (Puma concolor). Frequently seen avian species include turkey vulture (Cathartes aura), several raptors (hawks, osprey, and eagles), roadrunner (Geococcyx californianus), several owls, eight different woodpeckers, four species of wren, and four species of vireo. A large variety of other interesting Arizona wildlife species can be found within the park and offer year-round wildlife viewing opportunities.

Like many areas of Arizona, Tonto Natural Bridge State Park is also home to non-native plants and animals. These non-native species arrive in a variety of ways; some species have been accidentally introduced and humans introduced some purposefully. Himalayan blackberry (Rubus procerus) is a tasty example of non-native vegetation found in the park.

Key to Illustrations

Key to Illustrations